Re-imagining Middle-earth

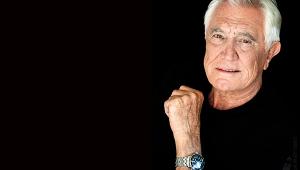

Joe Letteri has been responsible for the visual effects for many of the major box office blockbusters of the past two decades. The original Lord of The Rings trilogy, I, Robot, King Kong, Rise of The Planet of The Apes and this Summer’s Man of Steel are just some of the landmark titles that Weta Digital’s senior visual supervisor has toiled on.

Joe Letteri has been responsible for the visual effects for many of the major box office blockbusters of the past two decades. The original Lord of The Rings trilogy, I, Robot, King Kong, Rise of The Planet of The Apes and this Summer’s Man of Steel are just some of the landmark titles that Weta Digital’s senior visual supervisor has toiled on.

Letteri began his career as a CG animator on Steven Spielberg's Jurassic Park, before joining Weta via Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country and Casper. En route he has pocketed four Academy Awards and a quartet of BAFTAs, plus a rich assortment of other nominations and plaudits. Indeed, it’s another BAFTA bow that brings him to the UK. But he seems outwardly unflapped by the fuss. 'We don’t make these movies to win awards', he tells me.

Letteri claims he ended up in the special effects business in an ‘almost accidental’ way. Naturally he had a passion for fantasy and science-fiction films as a kid: ‘The original King Kong… the Harryhausen films… I loved watching Star Trek the TV series and 2001: A Space Odyssey blew me away. The idea that you could create worlds that were so believable that you felt like you were part of them, I just found that to be really interesting.’

But Letteri was also a maths whizz, and that provided his key to Hollywood’s virtual toy cupboard. ‘I was always interested in science, maths and perception,’ he says. ‘I wanted to know what makes something look real; what happens with light when you take a photograph. It turns out that the computer is a perfect tool for understanding and manipulating things like that. So my interests just sort of dovetailed.’ This fascination led him to pursue computer graphics, and he was eventually offered the opportunity to work on feature films.

With The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, Letteri and his team have polished their skills to baffling brilliance, as anybody who has picked up the recent Blu-ray release (reviewed here) will have seen. The only caveat is that this first release almost certainly won’t be the last for The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. Despite running to 169 minutes, there’s yet more to be seen. Exactly what, though, must remain a mystery for now. ‘Don’t ask Joe about the Extended Edition,’ I was warned prior to being ushered into his suite at Claridges.

It was a given that The Hobbit... would be considerably more complicated to make than previous LOTR outings. Peter Jackson’s decision to shoot in 3D while embracing HFR (High Frame Rate) 48fps cinematography mandated an almost Balrogian challenge. While ...Return of the King comprised 18,000 special effects shots, The Hobbit... demanded 22,000.

Of the two innovations, the move to stereoscopy was to provide the greatest consternation. The benefit of working in 2D, I’m told, is that you can fall back on old tricks. Not so with 3D: ‘You can’t cheat, because perspective is unforgiving,’ opines Letteri. ‘You have to be geometrically accurate. With stereo we had to invent new tricks.’ Traditional effects miniatures just didn’t work when shot in stereo; the need to maintain perspective was to prove a reoccurring shackle.

‘With 3D you really have to lock down exactly what the mood is and that requires you know exactly what the shots are,’ explains Joe. ‘But when you’re on an 18-month schedule where things are being shot out of order, the logistics of doing that become daunting.’ The solution, he notes, was to do a lot more in the digital domain. ‘It just becomes easier to create what you need, because then you have the flexibility to change your mind later.’

Even the familiar effect from the LOTR trilogy of Gandalf interacting onscreen with half-pint hobbits posed fresh problems when dimensionalised. The original films simply brought Gandalf closer to the camera and pushed Frodo back to make him appear smaller, a simple but effective piece of trickery. 'Only it doesn’t work in 3D,' says the VFX guru. Given that the opening act features elaborate interaction between a band of dwarves and one overlarge wizard, a new solution had to be devised. Weta fixed the problem by creating two sets side by side, one teeming with dwarves and the other a green screen set for Ian McKellen.

‘The dwarves were choreographed and knew their marks,’ recalls Letteri, ‘while Ian had C-stands representing the other actors.’ While the camera operators followed the hobbit action, a motion-controlled camera on the green screen set followed Gandalf. Jackson directed both simultaneously, a combined feed going to his monitor.

‘We ended up with this elaborate choreography to create a minute-long take of them walking through these two virtual worlds together. Amazingly we got it in four takes, but it took about a year to put it all together.’

When asked what he feels is The Hobbit...’s greatest FX achievement, Letteri says it’s the creation of the digital cast. ‘We’ve really brought characters off the page as J.R.R. Tolkien described them, in a way that ten years ago would have been almost impossible. I think the abilities developed over the years, to create characters and do scenes with them, has paid off here.’ He cites the use of HFR as having a beneficial impact on Gollum/Sméagol.

‘Gollum was our one speaking digital character in LOTR,’ recalls Letteri. ‘We had other creatures fighting battles but they really didn’t have to deliver lines. In The Hobbit, in addition to Gollum, we have five other speaking characters.’

According to Letteri, this is where the use of HFR really delivered. With the number of frames doubled, far higher detail became possible in the animation. ‘We could really sharpen up his movement and rapid-fire dialogue.’ The big pay off came in the subterranean showdown between Bilbo and Gollum, the Riddle in the Caves sequence. ‘If you look at that scene, that’s where it all came together. Because there’s less blur in the image, you perceive the detail all the way through; you can really pay attention to the nuance of the facial animation.’ The fact that Peter Jackson was able to write a nine-minute sequence in which Martin Freeman performed with a digital actor ‘is a great testament to what you can do with the art form these days.’

Perhaps surprisingly, HFR 48fps was a largely benign innovation. ‘It really didn’t affect us too much creatively,’ says Letteri candidly. ‘The obvious change was that we had twice as many frames to produce, so there was more work in that regard, and it did affect some of the departments that have to match things to the frame – like the camera department which has to lock camera movements frame to frame. But creatively, it really helped us, particularly with the animation.’

Of course, the task most likely to monopolise Letteri's time over the next few months is breathing life into the dragon Smaug, star of the sequel. ‘We’re only just starting to get to explore that. We saw Smaug briefly in the first film, but with these characters it’s only when you get into their major scenes do you allow yourself time to massage the design and make sure everything works.’ Indeed, it seems there’s an unenviable amount of work still to be done on the upcoming movies: ‘Most has been shot, although there is still more to shoot for the third film now that it’s a trilogy. But we still have the majority of visual effects to do for those two films.’

Despite the advances made in digital modelling, Joe Letteri doesn’t envisage a time when digital trickery will completely supplant physical effects. ‘There will always be a need for physical effects, especially where you need interaction with your actors,’ he says. ‘Even if we’re creating a digital character, Gollum being the perfect example, we still want to work with actors, because that physicality gives you that grounding in realism and emotion that would be lacking. I don’t think the art of traditional special effects will die out. You always need to bridge that gap between what’s real and what’s imaginary.’

|

Home Cinema Choice #351 is on sale now, featuring: Samsung S95D flagship OLED TV; Ascendo loudspeakers; Pioneer VSA-LX805 AV receiver; UST projector roundup; 2024’s summer movies; Conan 4K; and more

|